It’s no secret that for artists, altering the mind in one fashion or another is often regarded as a necessary or at least desired step in attempting to creatively express themselves, unearthing as it does an atypical way of thinking and seeing the world. Not all do this, but some.

And one might assume that this is a new phenomenon, dating to the 1960s or to the 1920s, times of decadence in experiencing the world and of creative explosion that coincided with the advent of relatively new substances to humankind- that artists of much earlier times did nothing like that.

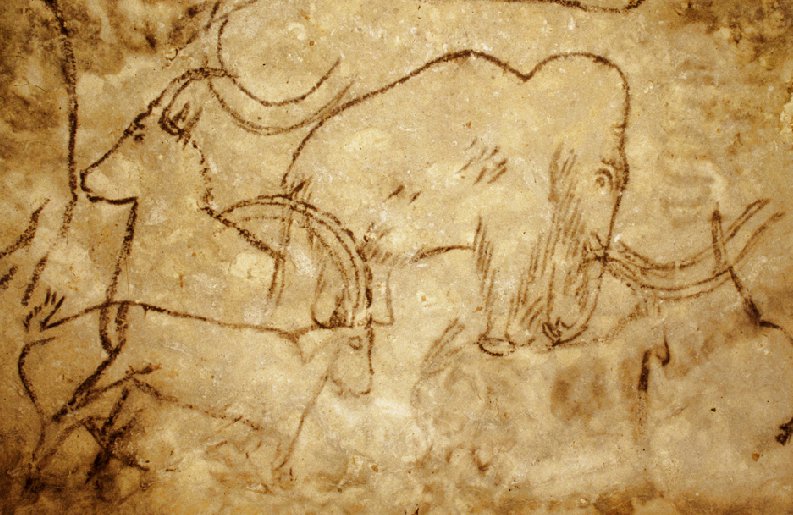

But new scientific research of caves in France where some of the most celebrated examples of surviving cave paintings exist suggests that that is precisely what the painters of ancient times did, upending many years of previous assumptions about their work processes, and creating some fascinating implications as a result.

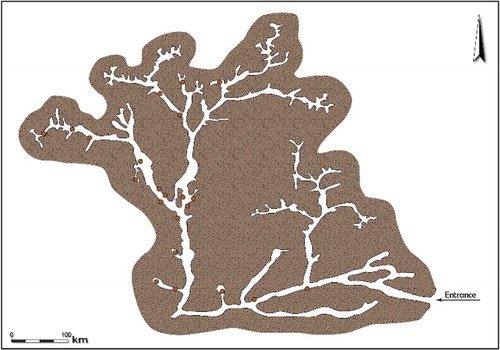

"A few years ago, as I was visiting some decorated caves in France, I started to notice that most images are found deep in very narrow caves," said archaeologist Yafit Kedar of Israel’s Tel-Aviv University. "I began to wonder why they chose to work this way, as opposed to paint at the entrance of wider caves, where they could have also enjoyed some natural light."

Kedar and her team began to examine the oxygen levels in those remote, narrow caves versus more open ones that would have afforded access to natural light, finding they could drop precipitously in just minutes- an effect that their modeling found was severely amplified by the use of oxygen-burning torches the cavemen would have required to navigate the caves and paint in them. Their conclusion was that this was deliberate.

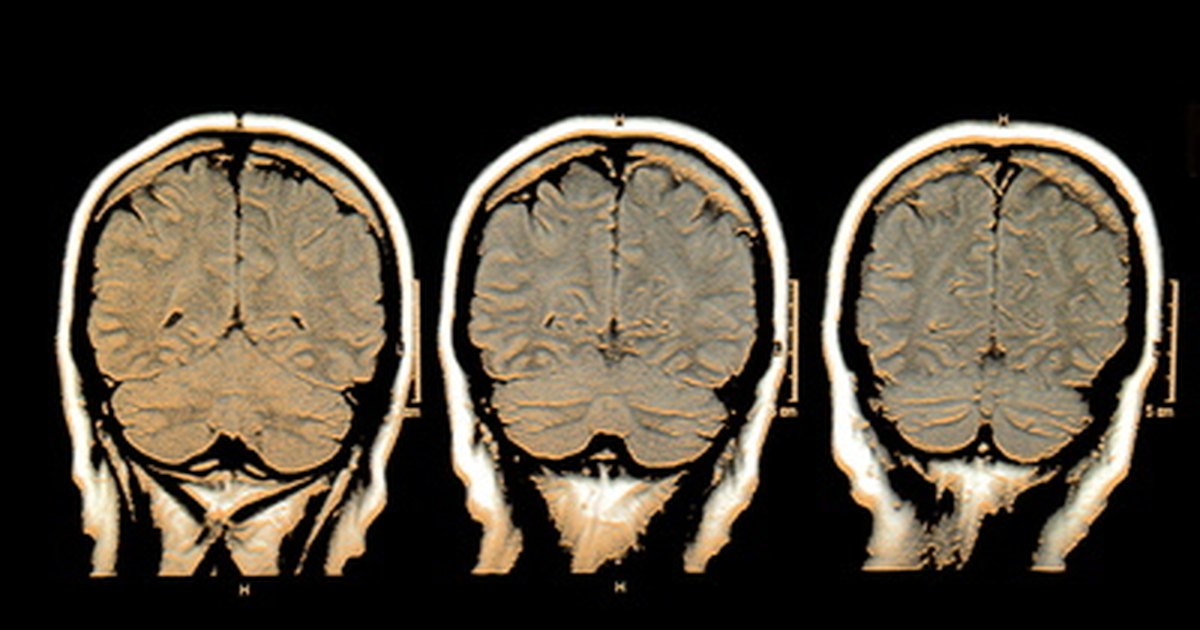

What the cavemen may have naturally intuited and chosen to seek out is something that modern science knows much more about and calls hypoxia, depravation of oxygen to the brain. Hypoxia naturally releases dopamine in the brain, which can cause drowsiness, euphoria and giddiness, hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. The overall effect would have been to send the cavemen on a mental trip that, whether deliberate or not, would have had an effect on the nature of the paintings they did.

Of course, other causes might exist for the deep placement of the art in the caves, such as the understanding that they might be preserved longer there, and the amplification of the oxygen drop could be an unintended and unavoidable consequences of bringing torches with them to light the way, but Kedar doesn’t think so.

Given the placing of paintings as far from cave entrances as it is possible for people to travel in, it is hard to dispute the Tel Aviv University team’s conclusions about the cavemen having sought those conditions in order to achieve the state that brought them inspiration otherwise unavailable in their day to day lives. The cavemen would have been unschooled and limited in raw mental material for art given limited travel and exposure to concepts outside their immediate existence.

Therefore it makes sense as a pragmatic decision barring further unearthing of evidence to the contrary, and what we are left with is the tantalizing idea that in a sense our forebears were more sophisticated than previously guessed, with a better understanding of their own consciousness and how it might be impacted by their actions.